Here is my original marker sketch of Esop.

Click any image for a larger view.

Click any image for a larger view.

I work in a very demanding environment. It is not uncommon for me to be working simultaneously on several complex and time-consuming projects all with tight deadlines, only to have someone come up to me and say, “We need such-and-such and we need it in an hour.” I know that I will certainly be asked to show Esop in different poses and from different angles and (9 times out of 10) my turnaround time will need to be immediate. In those situations, the well constructed vector file is my friend. Vector files are flexible, allow for easier revisions than other formats and are scalable to any size.

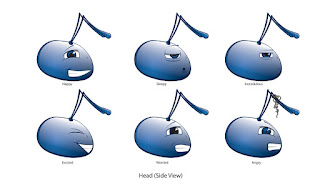

If you have ever played the game Cooties, by Hasbro, then you can understand the method by which I wanted to build Esop. I created multiple versions of his head, showing it from different angles and with different facial expressions. I did the same for his body and limbs. Again, click any image below to see a larger version.

Early on I provided several color variations

of Esop. Dark blue was the chosen color.

With a complete set of Esop parts, I – or any of my colleagues, regardless of their illustration abilities – can quickly and easily assemble Esop into any number of poses, shown from several angles, with different facial expressions.

Granted, since we use Esop in communications relating to our employee stock ownership plan, we hope to never have to show Incredulous Esop, or Worried Esop and certainly not Angry Esop (I didn’t even bother to make Sad Esop). Still, it is nice to have those options available and to be able to show Esop with a wide range of emotions.

May Esop’s face always have a smile!